Fauvism

and

the Wild Beasts of Early 20th Century Art

the Wild Beasts of Early 20th Century Art

the

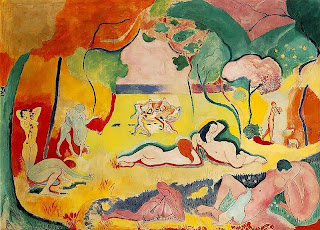

small group of artists who, shortly after the turn of the century, exploded

onto the scene with a wild, vibrant style of expressionistic art that shocked

the critics but has since been recognized as one of the seminal forces that

drove modern art.

They were called the fauves, French for "wild beasts", a term of derision used to indicate their apparent lack of discipline.

Today fauvism once thought of as a minor, short-lived, movement, is recognized as having paved the way to both cubism and modern expressionism in its disregard for natural forms and its love of unbridled color.

They were called the fauves, French for "wild beasts", a term of derision used to indicate their apparent lack of discipline.

Today fauvism once thought of as a minor, short-lived, movement, is recognized as having paved the way to both cubism and modern expressionism in its disregard for natural forms and its love of unbridled color.

The

Development of Fauvism

In a sense, Fauvism evolved from pointillism which, in turn, had evolved as a development of impressionism. The open-air paintings of the impressionists emphasized the way strong light broke up the uniform color of surfaces into shimmering bits of reflected color. They abandoned the carefully graduated tonal painting of the past and built their pictures with small brush strokes of pure color.

Pointillism took this further by painting with tiny dots of contrasting hues. Seurat, the greatest exponent of pointillism, held that each dot of paint should be accompanied by a weaker dot of its complement. Van Gogh had used some of the same techniques, but with much broader and bolder strokes.

Matisse dabbled in pointillism for awhile, but, his instinct was to make every stroke of his painting strong. He and his group developed a style of broad, short strokes of bright contrasting colors.

The new style that had been evolving for several years burst upon the public in October 1905 at the Salon d'Automne. To the traditionalists, the new style (embodying Derain's ideal of color for color's sake) seemed dangerous.

The paintings were hung together in the central gallery, surrounding a conventional renaissance-style statue. Tradition has it that art critic Louis Vauxcelles remarked of the situation: "Ah, Donatello au millieu des fauves. (Donatello among the wild beasts)" As the impressionists had before them, the fauves happily clung to the name that had been given to them as an insult.

In a sense, Fauvism evolved from pointillism which, in turn, had evolved as a development of impressionism. The open-air paintings of the impressionists emphasized the way strong light broke up the uniform color of surfaces into shimmering bits of reflected color. They abandoned the carefully graduated tonal painting of the past and built their pictures with small brush strokes of pure color.

Pointillism took this further by painting with tiny dots of contrasting hues. Seurat, the greatest exponent of pointillism, held that each dot of paint should be accompanied by a weaker dot of its complement. Van Gogh had used some of the same techniques, but with much broader and bolder strokes.

Matisse dabbled in pointillism for awhile, but, his instinct was to make every stroke of his painting strong. He and his group developed a style of broad, short strokes of bright contrasting colors.

The new style that had been evolving for several years burst upon the public in October 1905 at the Salon d'Automne. To the traditionalists, the new style (embodying Derain's ideal of color for color's sake) seemed dangerous.

The paintings were hung together in the central gallery, surrounding a conventional renaissance-style statue. Tradition has it that art critic Louis Vauxcelles remarked of the situation: "Ah, Donatello au millieu des fauves. (Donatello among the wild beasts)" As the impressionists had before them, the fauves happily clung to the name that had been given to them as an insult.

Fauvism

Fades as its Practitioners Evolve

By 1907, the major artists in the Fauve camp were beginning to evolve their styles in other directions. The influence of Paul Cezanne was having its effect on most of the artists of the early twentieth century.

In the paintings below, the bright colors and wild brush strokes of fauvism are giving way to the beginnings of the cubist and other modern movements.

By 1907, the major artists in the Fauve camp were beginning to evolve their styles in other directions. The influence of Paul Cezanne was having its effect on most of the artists of the early twentieth century.

In the paintings below, the bright colors and wild brush strokes of fauvism are giving way to the beginnings of the cubist and other modern movements.

Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954) and André Derain (French, 1880–1954) introduced unnaturalistic color and vivid brushstrokes into their paintings in the summer of 1905, working together in the small fishing

The Fauves were a loosely shaped group of artists sharing a

similar approach to nature, but they had no definitive program. Their leader

was Matisse, who had arrived at the Fauve style after earlier experimenting

with the various Post-Impressionist styles of Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne, and the Neo-Impressionism of Seurat, Cross, and

Signac. These influences inspired him to reject traditional three-dimensional

space and seek instead a new picture space defined by the movement of color

planes (1999.363.38; The Young Sailor I; 1999.363.41).

Another major Fauve was Maurice de Vlaminck (French, 1876–1958), who might be called a "natural" Fauve because his use of highly intense color corresponded to his own exuberant nature. Vlaminck took the final step toward embracing the Fauve style (1999.363.84; 1999.363.83) after seeing the second large retrospective exhibition of Van Gogh's work at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1905, and the Fauve paintings produced by Matisse and Derain in Collioure.

As an artist, Derain occupied a place midway between the impetuous Vlaminck and the more controlled Matisse. He had worked with Vlaminck in Chatou, nearParis , intermittently

from 1900 on ("School

of Chatou London

in a more restrained palette.

Other important Fauvists were Kees van Dongen, Charles Camoin, Henri-Charles Manguin, Othon Friesz, Jean Puy, Louis Valtat, and Georges Rouault. These were joined in 1906 by Georges Braque and Raoul Dufy.

For most of these artists, Fauvism was a transitional, learning stage. By 1908, a revived interest in Paul Cézanne's vision of the order and structure of nature had led many of them to reject the turbulent emotionalism of Fauvism in favor of the logic of Cubism. Braque became the cofounder with Picasso of Cubism. Derain, after a brief flirtation with Cubism, became a widely popular painter in a somewhat neoclassical manner. Matisse alone pursued the course he had pioneered, achieving a sophisticated balance between his own emotions and the world he painted.

The Fauvist movement has been compared to German Expressionism, both projecting brilliant colors and spontaneous brushwork, and indebted to the same late nineteenth-century sources, especially Van Gogh. The French were more concerned with the formal aspects of pictorial organization, while the German Expressionists were more emotionally involved in their subjects.

Another major Fauve was Maurice de Vlaminck (French, 1876–1958), who might be called a "natural" Fauve because his use of highly intense color corresponded to his own exuberant nature. Vlaminck took the final step toward embracing the Fauve style (1999.363.84; 1999.363.83) after seeing the second large retrospective exhibition of Van Gogh's work at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1905, and the Fauve paintings produced by Matisse and Derain in Collioure.

As an artist, Derain occupied a place midway between the impetuous Vlaminck and the more controlled Matisse. He had worked with Vlaminck in Chatou, near

Other important Fauvists were Kees van Dongen, Charles Camoin, Henri-Charles Manguin, Othon Friesz, Jean Puy, Louis Valtat, and Georges Rouault. These were joined in 1906 by Georges Braque and Raoul Dufy.

For most of these artists, Fauvism was a transitional, learning stage. By 1908, a revived interest in Paul Cézanne's vision of the order and structure of nature had led many of them to reject the turbulent emotionalism of Fauvism in favor of the logic of Cubism. Braque became the cofounder with Picasso of Cubism. Derain, after a brief flirtation with Cubism, became a widely popular painter in a somewhat neoclassical manner. Matisse alone pursued the course he had pioneered, achieving a sophisticated balance between his own emotions and the world he painted.

The Fauvist movement has been compared to German Expressionism, both projecting brilliant colors and spontaneous brushwork, and indebted to the same late nineteenth-century sources, especially Van Gogh. The French were more concerned with the formal aspects of pictorial organization, while the German Expressionists were more emotionally involved in their subjects.

Between 1901 and 1906, several comprehensive exhibitions

were held in Paris, making the work of Vincent

van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Paul

Cézanne widely accessible for the first time. For the painters who

saw the achievements of these great artists, the effect was one of liberation

and they began to experiment with radical new styles. Fauvism

was the first movement of this modern period, in which color ruled supreme.

The advent of Modernism is often dated by the appearance of the Fauves in Fauvism was a short-lived movement, lasting only as long as its originator, Henri Matisse (1869-1954), fought to find the artistic freedom he needed. Matisse had to make color serve his art, rather as Gauguin needed to paint the sand pink to express an emotion. The Fauvists believed absolutely in color as an emotional force. With Matisse and his friends, Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) and André Derain (1880-1954), color lost its descriptive qualities and became luminous, creating light rather than imitating it. They astonished viewers at the 1905 Salon d'Automne: the art critic Louis Vauxcelles saw their bold paintings surrounding a conventional sculpture of a young boy, and remarked that it was like a Donatello ``parmi les fauves'' (among the wild beasts). The painterly freedom of the Fauves and their expressive use of color gave splendid proof of their intelligent study of van Gogh's art. But their art seemed brasher than anything seen before.

During its brief flourishing, Fauvism had some notable adherents, including Rouault, Dufy, and Braque. Vlaminck had a touch of his internal moods: even if The River (c. 1910; 60 x 73 cm (23 1/2 x 28 3/4 in)) looks at peace, we feel a storm is coming. A self-professed ``primitive'', he ignored the wealth of art in the Louvre, preferring to collect the African masks that became so important to early 20th-century art.

Derain also showed a primitive wildness in his Fauve period--